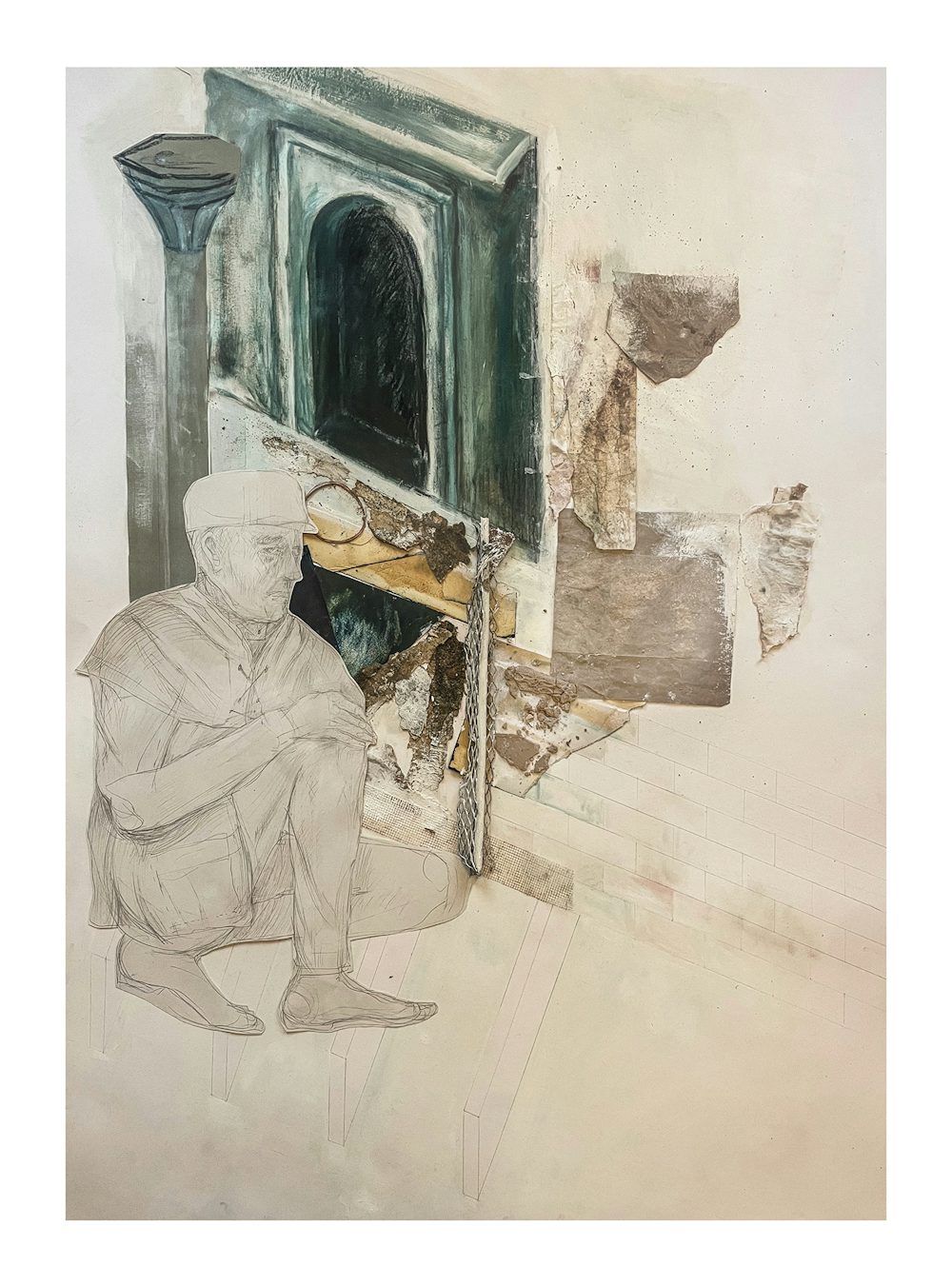

This project employs analogue drawing methods and found materials to examine the remnants of Smithfield Market’s past. By isolating and reassembling fragments of the building—such as worn stair treads, rusted supports, and chipped tiles—through collage, the drawings offer a new interpretation of the site’s history. The goal is to bring visibility to the erased histories of the market, focusing on the lives of displaced tradesmen, porters, and butchers. Drawing becomes a form of remembrance, resonating with Walter Benjamin’s idea: “The past that is not recognised in its entirety will continue to haunt us,” 1 allowing these hidden histories to resurface through the materials themselves.

Smithfield's prominence grew in the 14th century when livestock slaughter was banned within the City walls, and the Corporation of London granted formal approval for a weekly market. Tradesmen, including butchers, began their routines in the early hours, preparing stalls, sharpening knives, and arranging cuts of meat. Bumarees, responsible for transporting goods, carried heavy loads between stalls, slaughterhouses, and storage areas. The market buzzed with activity, with the labor of butchers and porters shaping its rhythm throughout the day. Their routines maintained the market’s operation until its closure in the late afternoon, contributing to the city’s food supply.

The building is currently under redevelopment into a museum, with the City of London compensating tradesmen who refused to leave. The history of the market has been cut short. Is documenting the current traces on-site a way to repair that history? This act of repair addresses an ‘erased history.’ We understand visibility and invisibility as linked to power,2 and there is a certain violence in erasing history. Collecting and remembering becomes an act of repair. Through drawing, I aim to illuminate the past life of the building and the erased history of the Meat-market since 1100. Traces of demolished elements remain on the spine-wall, eventually covered by new finishes, providing insight into the routines of displaced tradesmen, bumarees, and butchers.

Drawing becomes a tool for repair—an active form of remembering that goes beyond mere documentation. Through the process, detached fragments and remnants of the building can be re-imagined and re-enacted, reviving the lost history of the market. Traces of worn stair treads, rusted supports, and chipped tiles speak not only to the architecture but to the lives of its former users. By isolating and arranging these materials, the drawing transforms into a storytelling device, contributing to the building’s mosaic of lived experience.

The material—the traces left by tradesmen, butchers, and porters—becomes a metaphor for memory, holding the stories of everyday labor and commerce. As Giorgio Agamben suggests, “Remembrance restores possibility to the past, making what happened incomplete and completing what never was. Remembrance is neither what happened nor what did not happen but, rather, their potentialization, their becoming possible once again.”3 The drawing reintroduces erased histories, offering a way to imagine the past in its full potential, capable of transformation and reanimation.

The market’s detached fragments—worn stair treads, rusted supports, and chipped tiles—become artefacts holding the echoes of past activity. These fragments act as "episodes" in the building’s history, their surfaces speaking to the labor of butchers, porters, and tradesmen. By isolating and arranging these materials, the drawing becomes a dynamic storytelling device, where each piece contributes to the building’s narrative.

Following Rena Papaspyrou’s approach, the material’s associative potential becomes central. Traces of wear, scratches, stains, and patinas become "images in matter"—abstract yet evocative impressions inviting viewers to imagine the human activities that shaped them.4 These marks suggest the butcher’s rhythm, the porter’s weight-laden movements, or the countless steps that shaped the market’s floors. Drawing these elements reanimates the building’s history through its material memory, reviving what has been erased.

Using Gordon Matta-Clark’s collage techniques emphasizes the fragmented, layered nature of the market’s history. By assembling detached elements—whether drawn, photographed, or derived from material scans—into a composition, the drawing simulates the site’s multidimensional space and time. Overlapping planes represent both physical spaces and temporal shifts, while negative spaces allude to what has been erased. The collage becomes a map of the material’s associative connections, depicting the market’s architecture and revealing the interplay between human and material stories.

The drawing’s surface becomes a dynamic stage where materials, marks, and fragments interact, telling their stories. This allows the site’s "episodes" and "images in matter" to coexist and inform one another.

Layering within the composition suggests depth, with some market elements fading into the background to represent forgotten histories, while others emerge vividly to assert their presence. Contrasting human-made marks with organic decay, the traces of labor align with the materials’ natural aging, emphasizing the passage of time and its effects on the site.

The market’s textures and details—whether through mixed media or material scans—evoke its tactile qualities and the history of its users.

Through these processes, drawing becomes not only an act of remembering but a tool for repair, reintroducing the erased histories of Smithfield Market. By depicting the lives and labor of the market’s former users through their material traces, the drawing bridges past and present, making the invisible visible once again.

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, 1968, p. 255 ↩

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1975, p. 200. ↩

Giorgio Agamben, The Remains of the Day, 1999, p. 56. ↩

Papaspyrou, R., 2011. Images in Matter: Materiality and Memory in Drawing. In: Art and Architecture Journal. 24(3), pp. 46-62. ↩