Media Studies

Situated in the Royal College of Art School of Architecture and welcoming a student cohort from across multiple spatial design disciplines, Media Studies provides a rigorous and granular examination of historical and contemporary methodologies of media research and practice.

Our collective goal is to increase critical engagement with media.

We achieve this through lectures, tutorials, and workshops in which new approaches to media are conceptualised, refined, and implemented in innovative proposals and projects. Further, Media Studies is focused on non-representational media, stepping aside from traditional architectural media such as scaled drawings, models, and renderings, and instead applying our research to the creation of discrete media objects.

In other words, this unit is not interested in projective media that represents proposed buildings or environments. Robin Evans famously stated that “architects don’t build buildings, they make drawings”1, in other words, an architect’s practice is centred on the drawing or the representation of a building or space, not the actual building or space. Today, we could expand this observation to include contemporary representational media such as digital environments, static and dynamic analogue and digital renderings, or video and moving image, but Evans’ observation remains correct. Similarly, the media used to describe an academic project is not the building (or interior or city), it is a scaled representation, an abstracted approximation. In recent years the academic design studio has greatly expanded the range of media it deploys, but its representative nature remains. Both the professional and the student assemble media to allow those who are fluent in this language to interpret these abstractions and conflate the various drawings, models, or images into a mental composited image of the final construction. All of this is a complex, discipline-specific media process based firmly in representation.

However, media can also be non-representational.

For example, a photograph can be interpreted as a non-representational, discreet media object; most photographs are not photographs of projected future photographs. One could argue that a contact sheet or the digital interface in Bridge or Lightroom are representations of a future photograph. But the actual photograph (whether it’s analogue or digital) is a unique object with its own embedded meaning whose context is dependent on the human or machine that made the image, the time in which it was produced, its cultural location, its political consequence, etc. The photograph just is. Similarly, a painting, a performance, a handmade book or an illustration is rarely – if ever – attempting to suggest the intention of another media type. While there are always exceptions to these rules, in Media Studies we will endeavour to make work that is non-representational.

What does this mean and why is it important?

Media Studies provides a space where media experimentation can take place outside of the design studio and its demands for representation. To do this we must first establish our own context and the range of work that we will engage. This is achieved by implementing the cumulative knowledge shared and discussed in our lectures and tutorials. It manifests in the projects that are created and finally tested by our collaboration with external professionals and academics. Media Studies will challenge you to create discreet media objects (film, books, sculpture, performance, text, photography, digital objects or environments, exhibitions, situations, etc.) that are representative only of themselves, whose meaning resides in the media. We will research non-representational media and the artists, designers, architects, and theorists that make and write about such work. We will create projects that challenge or strengthen those positions. We will experiment with media for the sake of the media. We will create projects that sit between, outside, or in opposition to disciplines, focusing on media as a primary site and material of and for experimentation. We will investigate the emancipatory possibilities of media. We will acknowledge media’s complicity in processes of oppression, colonisation, and imperialism, and we will work to challenge and contest these realities.

Each year, we choose a conceptual scaffold to structure our research and projects. The theme this year is failure, impossibility, and the unknown.

2024/25 Course Description: Failure, impossibility, and the unknown

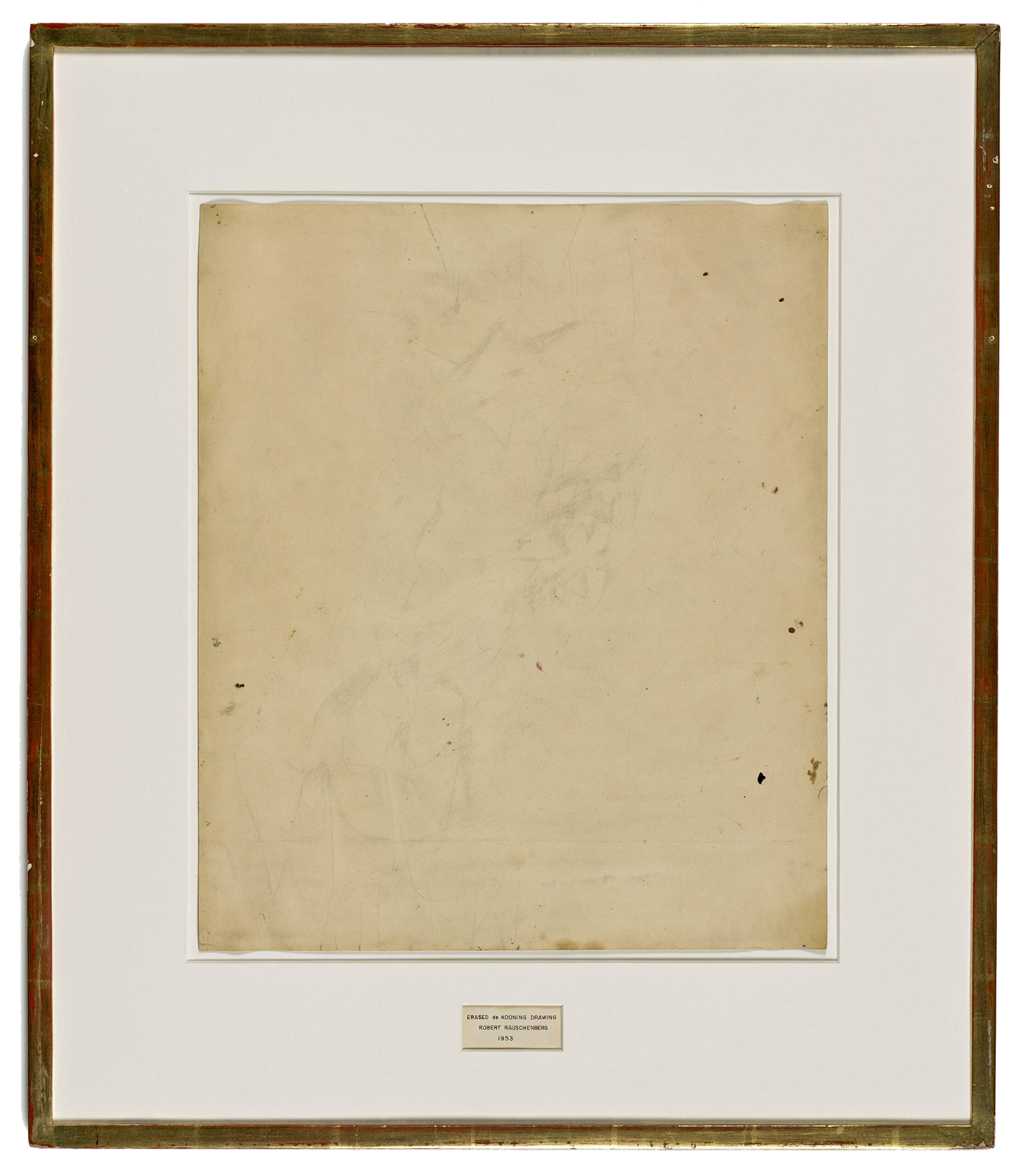

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953

In 1953, 27-year-old artist Robert Rauschenberg approached the studio of famed abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning with an absurd request. At the time, de Kooning was an internationally recognised artist at the top of his career, while Rauschenberg was at the beginning of his. Rauschenberg had been working on furthering his experimentations in abstraction, including an extensive series of monochromatic black and white paintings. His path led him to the point where he was asking his friends, including Cy Twombly, to paint his paintings for him, challenging ideas of authorship and authenticity. His progression involved acts of negation and removal, including erasing his own drawings and paintings, literally removing authorship. He found erasing his work was unsatisfying. “If it was my own work being erased, then the erasing would only be half the process…”2 In other words, if he was both drawing and erasing, then the erasing would be only a part of the work, instead of the entire work. He realised the subject of his erasures needed to be created by someone important, a work whose removal would be a shock. “I realized that it had to be something by someone who everybody agreed was great, and the most logical person for this was de Kooning.” 3 He asked de Kooning.

“I remember that the idea of destruction kept coming into the conversation, and I kept trying to show that it wouldn’t be destruction,” said Rauschenberg, “although there was always the chance that if it didn’t work out there would be a terrible waste.”4 De Kooning was initially hesitant, but, as Calvin Tomkins wrote in a New Yorker profile in 1964, he eventually agreed to the idea and began searching his archives for an appropriate work. Later, he would say that he wanted to choose a drawing that he would “miss”, supporting the concept that Rauschenberg was desiring.

It took months for Rauschenberg to erase the drawing, but the resulting work, Erased de Kooning Drawing, wasn’t immediately recognised, or even exhibited. It wasn’t until 1964 that the work became a sensation

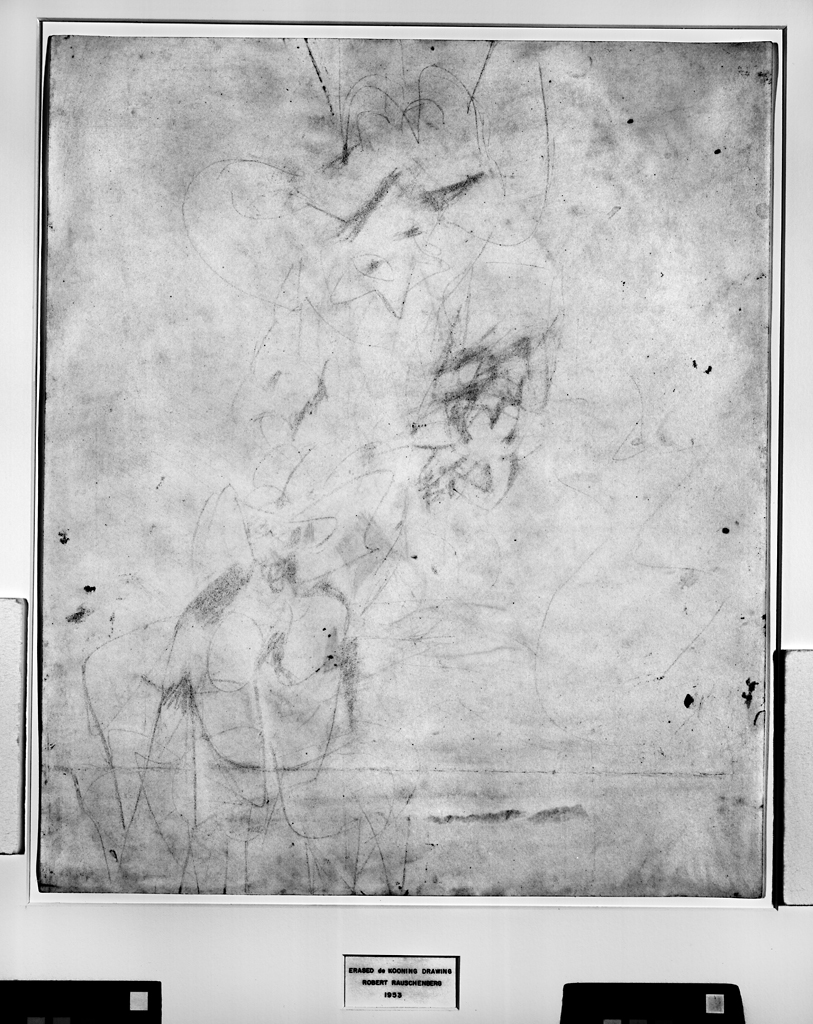

X-ray scan of Erased de Kooning, perhaps revealing some of the original content of the drawing

Today, the act of destroying – much less modifying – a valuable work by one of the world’s leading artists seems unimaginable. In fact, savvy activists have realised the best way to get instant exposure is to vandalise a prominent work of art held by a wealthy collector. And despite some contemporary artists’ efforts to devalue their work through reproduction or self-sabotage, these acts often lead to increased exposure, value, and status, greedy collectors refusing to allow anything to negatively impact their investment.

The impossibility of erasing a de Kooning is only increasing, not only in economic terms, but also in our contemporary reality of perpetual safeguarding. We’ve been conditioned to preserve everything, to archive even the most banal objects and moments. Our devices are laden with tens of thousands of images we’ll never see, our apps are replete with endless chats, overloaded with millions of words of nothing, kept and stored forever.

Rauschenberg’s actions show a bold young artist struggling to find a place in an art world expanding uncontrollably and the reality of Abstract Expressionism being co-opted by western governments as a metastasised iteration of Cold War colonialism. Injecting failure into the process of his art making created an unknown outcome, one in which even the Rauschenberg acknowledged that it could have gone terribly wrong.

What does it mean to remove, to purposefully negate a creative act with little confidence that the result will create new meaning? How does speeding up the processes of entropy become an act of production? How can we harness impossibility as inspiration?

This year in Media Studies we will study projects in which failure is embraced, in which impossibility is encouraged. We will challenge each other to take risks, to empty our cache, to delete our chats, and to find meaning in the unknowable.

Or as Fugazi sang in 1995, “I’m a failure, not your failure now.”