Serena Walker

"Land Beyond the Face"

Section MS1, Georgia Hablutzel

Keywords: landscape, history, identity, book, publishing, language

This project investigates how nostalgia and artistic representations of the British landscape shape our perceptions of nature, focusing on the tension between detachment and immersion. Its stem from The Face of the Land, a 1931 publication by George Allen & Unwin in collaboration with the Design and Industries Association. This book sought to present a typical vision of Britain through carefully curated photographs. While claiming to be chosen without favour or prejudice , these images reflect a highly subjective framing of heritage, idealizing and selectively recalling the past to create a landscape that feels timeless yet detached from its ecological realities.

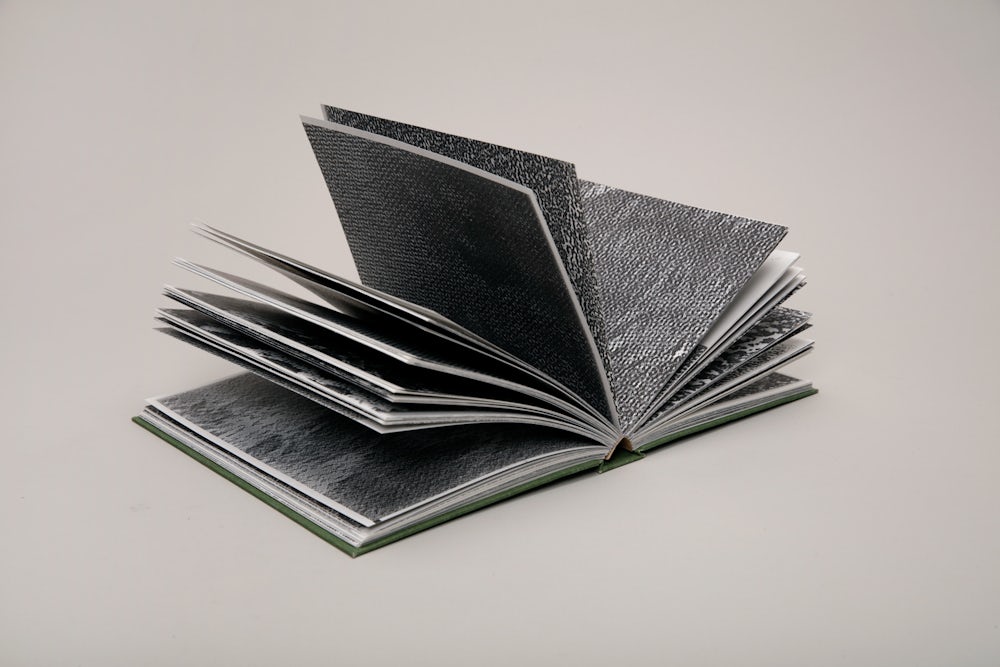

Using The Face of The Land as a site of interpretation the project fragments these images to reflect the commodification of nature while inviting a more reciprocal and immersive interaction with it. Using the form of traditionally bound books in a slipcase, mimicking The Face of the Land to critique how landscapes are idealized and reproduced, often through nostalgic, classically British frames. Placed on a pedestal, the books are both objects of reverence and a critique of the fragile, mediated narratives we impose on the land. The physical act of reading these books requires direct interaction, further dissolving boundaries. However, the pages are photocopied, making them fragile and prone to smudging and fading with touch, emphasizing the corrosive effects of reproduction due to human interventions.

Linear perspective, historically used in art and photography, plays a key role in our detachment from the landscape. By establishing a division between the observer and the observed, it positions the landscape as something to be viewed, controlled, and consumed. This conceptual distance allows the land to be commodified, transforming it into a consumable aesthetic object. The Face of the Land exemplifies this dynamic: its photographs, shaped by the resolution of the camera, their framing, and their placement on the page, become interchangeable with both the physical landscape and traditional British paintings, like those by Constable. Just as Constable’s brushstrokes define the resolution of his work, the camera lens defines the photographs, reducing them to staged and curated constructs.

What does it mean to truly engage with a landscape on a 1:1 scale, free from traditional frames of reference? This question drives the project, which uses the processes of photocopying and zooming to interrogate how we represent and consume the natural world. The photocopier—a tool of mass production—homogenizes resolution, stripping away original textures and details. By fragmenting and distorting landscape imagery, the project aims to dissolve the boundaries between observer and observed, challenging the detachment fostered by traditional linear perspective. Yet, photocopied pages are fragile, fading and aging far faster than photographs, underscoring the transience of the landscape.

In contrast, modern technologies like 3D scanning and Google Earth offer hyper-detailed, digitized wholes of landscapes, accessible entirely online. The project’s second book replaces The Face of the Land’s photographs with Google Earth screenshots that match the descriptions, while also highlighting humorous contradictions within the original text. By juxtaposing analog processes with digital resolutions, the project critiques nostalgia’s role in shaping our relationships with the natural world and asks what it means to truly experience the landscape in an era dominated by both idealized heritage and digital mediation.