Media Studies

Situated in the Royal College of Art School of Architecture and welcoming a student cohort from across multiple spatial design disciplines, Media Studies provides a rigorous and granular examination of historical and contemporary methodologies of media research and practice.

Our collective goal is to increase critical engagement with media.

We achieve this through lectures, tutorials, and workshops in which new approaches to media are conceptualised, refined, and implemented in innovative proposals and projects. Further, Media Studies is focused on non-representational media, stepping aside from traditional architectural media such as scaled drawings, models, and renderings, and instead applying our research to the creation of discrete media objects.

In other words, this unit is not interested in projective media that represents proposed buildings or environments. Robin Evans famously stated that “architects don’t build buildings, they make drawings”1, in other words, an architect’s practice is centred on the drawing or the representation of a building or space, not the actual building or space. Today, we could expand this observation to include contemporary representational media such as digital environments, static and dynamic analogue and digital renderings, or video and moving image, but Evans’ observation remains correct. Similarly, the media used to describe an academic project is not the building (or interior or city), it is a scaled representation, an abstracted approximation. In recent years the academic design studio has greatly expanded the range of media it deploys, but its representative nature remains. Both the professional and the student assemble media to allow those who are fluent in this language to interpret these abstractions and conflate the various drawings, models, or images into a mental composited image of the final construction. All of this is a complex, discipline-specific media process based firmly in representation.

However, media can also be non-representational.

For example, a photograph can be interpreted as a non-representational, discreet media object; most photographs are not photographs of projected future photographs. One could argue that a contact sheet or the digital interface in Bridge or Lightroom are representations of a future photograph. But the actual photograph (whether it’s analogue or digital) is a unique object with its own embedded meaning whose context is dependent on the human or machine that made the image, the time in which it was produced, its cultural location, its political consequence, etc. The photograph just is. Similarly, a painting, a performance, a handmade book or an illustration is rarely – if ever – attempting to suggest the intention of another media type. While there are always exceptions to these rules, in Media Studies we will endeavour to make work that is non-representational.

What does this mean and why is it important?

Media Studies provides a space where media experimentation can take place outside of the design studio and its demands for representation. To do this we must first establish our own context and the range of work that we will engage. This is achieved by implementing the cumulative knowledge shared and discussed in our lectures and tutorials. It is tested by our collaboration with external professionals and academics, and finally in the projects that are created. Media Studies will challenge you to create discreet media objects (film, books, sculpture, performance, text, photography, digital objects or environments, exhibitions, situations, etc.) that are representative only of themselves, whose meaning resides in the media. We will research non-representational media and the artists, designers, architects, and theorists that make and write about such work. We will create projects that challenge or strengthen those positions. We will experiment with media for the sake of the media. We will create projects that sit between, outside, or in opposition to disciplines, focusing on media as a primary site and material of and for experimentation. We will investigate the emancipatory possibilities of media. We will acknowledge media’s complicity in processes of oppression, colonisation, and imperialism, and we will work to challenge and contest these realities.

Each year, we choose a conceptual scaffold to structure our research and projects. The theme this year is distribution.

2022/23 Course Description: Distribution

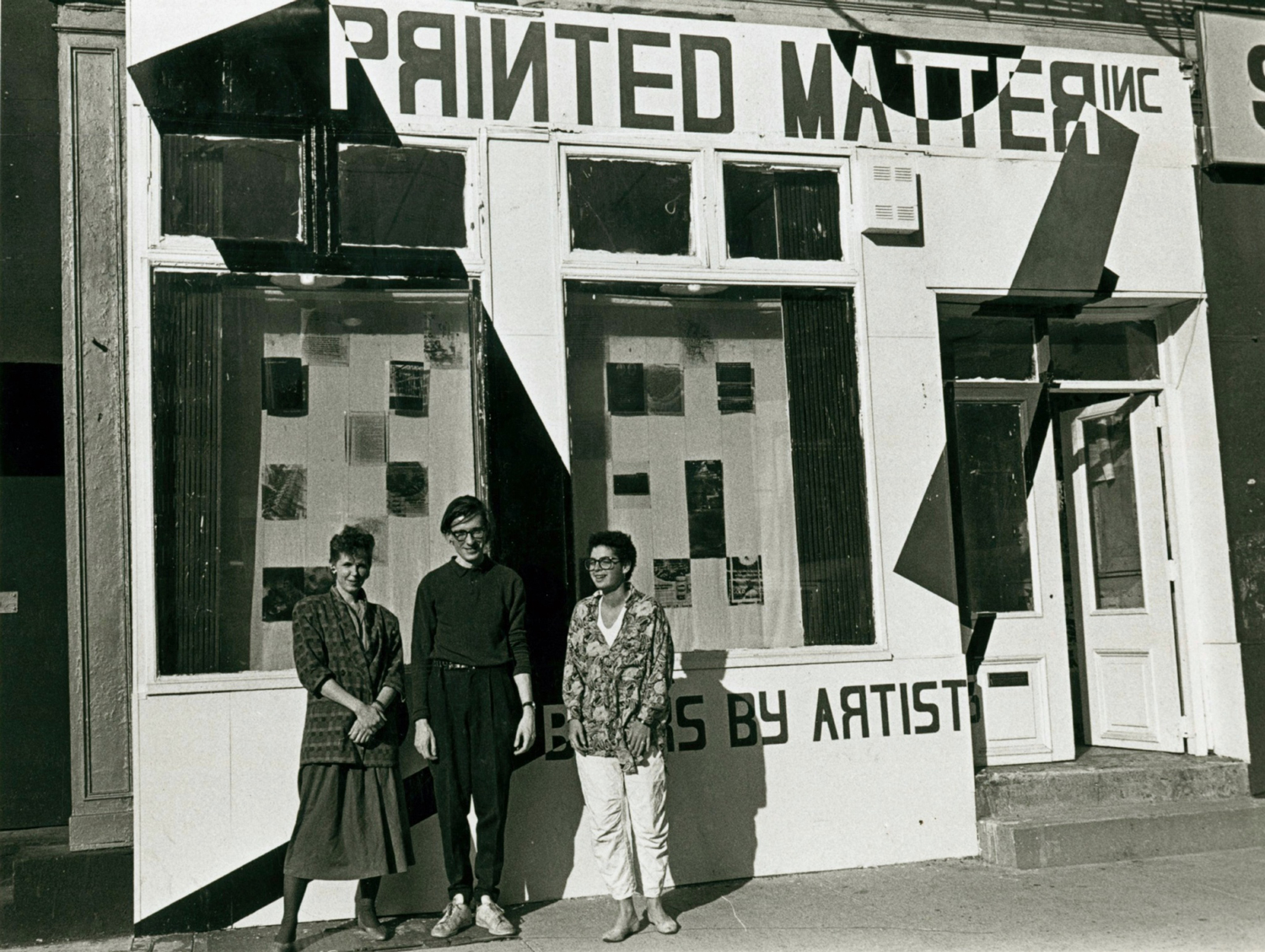

Printed Matter artist-run bookstore in its original location, New York, USA

In the summer of 2022, social media giant Instagram introduced sweeping changes to the types of media it prioritises. Short videos, portrait-oriented and full screen, were given algorithmic preference over static images and slideshows. Sponsored posts and suggested accounts were highlighted over those by users’ friends or family members. The outcry was immediate, petitions were created, social media was flooded with users lamenting their loss. At the forefront of the criticism was the demand that Instagram stop mimicking TikTok and for its parent company Meta to “Make Instagram Instagram Again”2. In response, the head of Instagram Adam Mosseri tweeted that the changes were a result of “the growth in photos and videos from friends” being primarily “in stories and in DMs”3. While his use of the word growth could be interpreted as a simple reference to the actual number of photographs and videos being posted to the platform, it was clear he was also referring to the growth of Instagram as a company. By referring to the company’s economic strategies with the public, Mosseri implied that Instagram’s financial growth was a shared concern. Are we, the public, responsible for assisting in a company’s economic growth? Does our use of mainstream media platforms equate to our complicity in their financial wellbeing?

This raises a fundamental question for media-based practitioners: what methods should we use to distribute the work we create? At the core of the Instagram outrage is the increasingly blurry line between a dominant method of distribution (Instagram) and the user’s complicity in its business practices. This is a contemporary phenomenon. We need to look back only 20 years to see a completely different media distribution landscape. The media ecology once included an array of magazines and publishers, independent bookstores, community-run civic centres, individually owned and maintained websites, local fanzines and ad hoc publishing, independent journalists and writers, and on and on. While there are still thriving examples of these distribution nodes still active, for the most part they have been replaced by Spotify, Instagram, TikTok, and the like.

A common response to criticism of online monopolies is that the distribution provided by these services has an overall positive effect; that these platforms have democratised distribution. That the negative aspects of the platforms are justified because of the enormous, previously unimaginable audiences now accessible to individual musicians, artists, etc. This is convincing and some of the changes to the music industry support these claims. However, this argument also assumes that all media – and the individuals, organisations, collectives, or groups that make media – are already global and are simply waiting for exposure. Further, it assumes that for something to be “successful” it has to be mainstream and have achieved global acceptance. This argument assumes – in a very neo-liberal sense – that everyone is on the verge of fame.

Ed Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966

Artists and musicians are now forced to share distribution space with global brands, celebrities and billionaires, and nearly every politician in the world regardless of ideology. Posts that feature art or music or culture appear alongside advertisements for housewares, “content creators” endlessly mimicking one another, and a steady onslaught of traumatic breaking news alerts. Users are forced to consume an endless stream of media in hopes of occasionally seeing something they like. For Internet natives this is might seem normal and perhaps it could be another characteristic of the “level playing field” discussed above. However, it begs another important question: can a generic online platform simultaneously promote the work of an independent artist and a multi-national corporation? If the answer is yes, if our work can sit comfortably next to that of companies and individuals that we are fundamentally opposed, have we lost our criticality? Or has criticality evolved?

The lectures for Media Studies this year will explore historical and contemporary media distribution methods and critically examine how these systems work, who benefits from specific networks, and how they can be re-imagined. We will dissect the connectivity between independence and corporation, between DIY ethics and commercial mass marketing. Of special note will be research into understanding how artists (architects, designers, writers, producers, musicians, etc) function outside the systems of mass media through artists’ books, independent venues and collectives, self-publishing and production, record pressing, zines and DIY media objects, artist run initiatives and galleries, and so on. Who creates and manages these systems? Does the method of distribution relate to the material being disseminated? Where does criticality lie when the majority always rules?

Can 50,000,000 fans, in fact, be wrong?

David Burns, Media Studies Lead

Evans, R. (1996) "Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays". London: Architectural Association Publications. ↩

A disturbing parallel to right-wing American politics that indicates the populist nature of social media. ↩

Mosseri, A. (2022) [Twitter] 26 July. Available at: https://twitter.com/mosseri/status/1552000469681184772 (Accessed 14 August 2022). ↩