Rita Louis

"Palimpsest I"

Keywords: feminist methodologies, body, objects, narrative, decolonising knowledge, materials

My project concerns the gender bias within the textile industry in India. It speaks about the nature of textiles, the labor associated with it and the body (women) as a living archive of the collective trauma.

Textiles are deeply linked to certain places and associated with specialist skills.They are a palimpsest of our past, present and future. They are a socially dynamic, communicative and active material that offer a rich seam of inquiry into how clothing participates and influences how we live.

India has a rich textile heritage, in fact the country has an artisanal textile tradition that dates back to the third century. The Indian handloom sector is not just the largest source of employment and income generation, it is also the one area of acknowledged skill, creativity and expertise where India is not just at par with, but unique in the rest of the world. From the vibrant and varied weaves being woven in every part of the country to the equally varied skills of block printing, bandhini, patchwork, embroidery, Kancheevaram sarees or even the humble Khadi (Freedom Fabric).

However, women form over 50% of the workforce in the textile sector of India. They spend long hours crafting garments which takes a toll on the body. Despite this, their earnings are minuscule - most of them still earn less than the stipulated minimum daily wage. Women are concentrated in lower forms of technology which could be small scale power looms or handlooms production, which permit labor - intensive production processes. There is substantial empirical evidence that women’s labor is inexpensive and it works to the advantage of employers and contractors to employ them. Where there is production accesses to family labor, women seldom get paid for their labor.

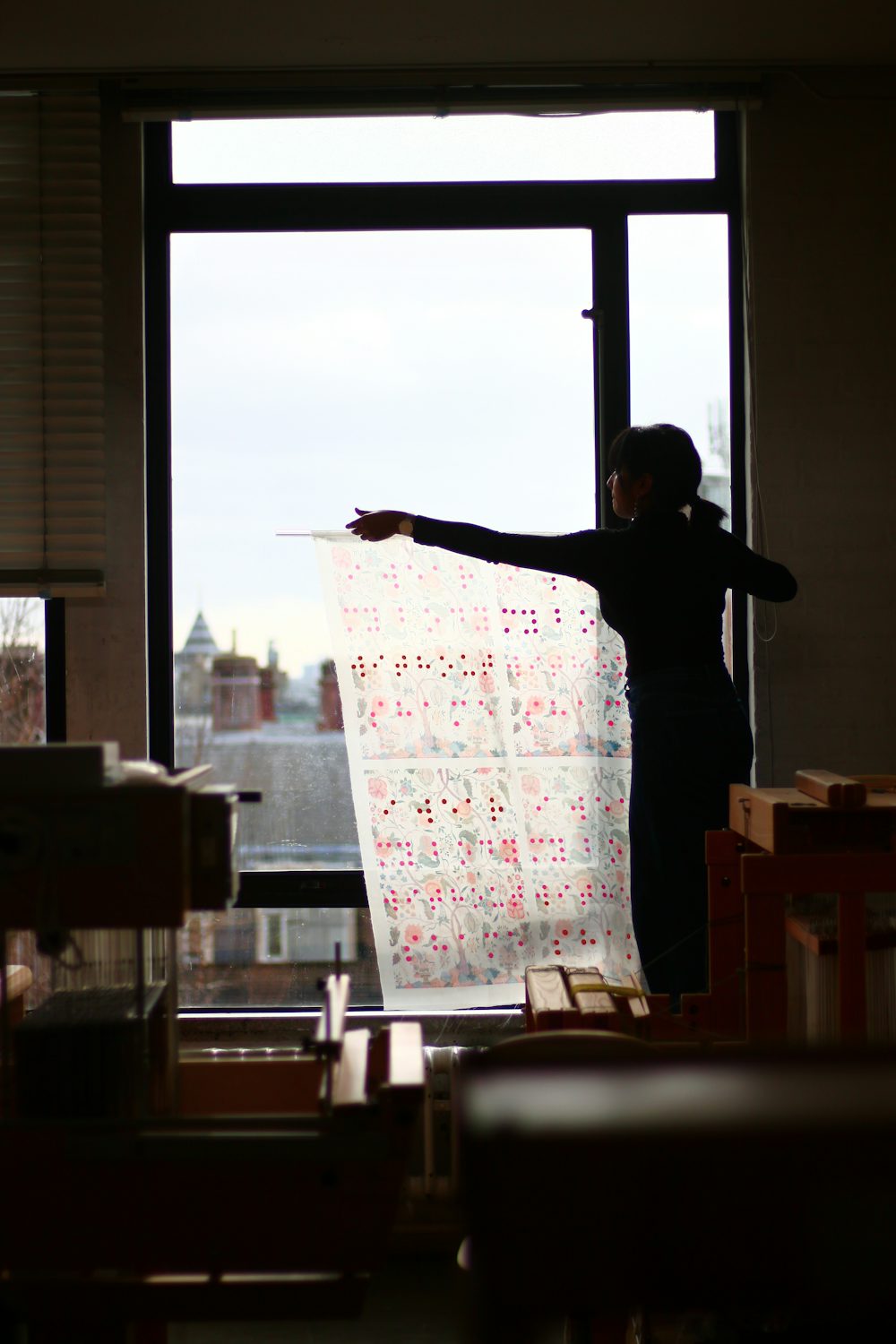

The process of mediation began with the photogravure of a Bengali woman at the spinning wheel by Martin Hurlimann. I looked closely at the woman, noticing how the act of weaving is associated with her body. Later on, using my mother’s saree with a traditional Indian print as a source, I reimagined four identical patterns to form a shawl worn by women in India. The shawl is overlaid with an embroidered chant in Braille; the red dots are symbolic and represent the bindis worn by the conscientious women workers. The chant reads: I wear my body without shame.

Through repetition, I question the nature of the labor intensive, handcrafted textiles often floating as a banal wreath of fabric tussle. The dotted pattern forming the chant in braille disallow easy access to the content of the text, much like their cries of help that are never seen but only felt …