My project focuses on orientalism. I am concerned with how the recontextualisation of Eastern architectural styles in the West, alters their cultural meaning and history. In doing so, I examine how Iznik tiles have been introduced in the private Western setting as a colonial practice.

Due to their intertwined history and cultural interactions; subjects and styles from the East were reappropriated in the West since the 15th century. Sometimes exact copies were made, at other times the sources were referenced to create hybrid objects. The fascination with the “exotic” East played a role in this as “the Other” was found different and romanticised by the West.1

In the 18th century, architects and theorists confronted with the dominance of classicism, turned to fresh sources of inspiration as a means of satisfying their wealthy clients’ demands. The taste for the “exotic” seemed just the thing for stimulating the imaginations of those who designed interiors and those who lived in them. Chinese salons, Turkish boudoirs and Persian bedchambers all made their appearance in private buildings.2 The Victorian home began to embody the look of the Orient itself, with an excess use of textiles, tiles and glassware. An unapologetic luxury, mirroring the East.3

The art of the Ottoman Empire and especially the Iznik tiles provide a theatre to observe this interaction between East and West. In the 17th century the popularity of Iznik wares in Europe led to various attempts of its imitations as well as the use of them in architectural settings.4 The Iznik tiles in the East were primarily produced for the court of the Ottoman Emperor and monumental buildings such as mosques or palaces. They were not used extensively on the facades nor on interiors of houses. Unlike in the West, the Iznik tiles are exclusive decorative elements made with a lot of craftsmanship.

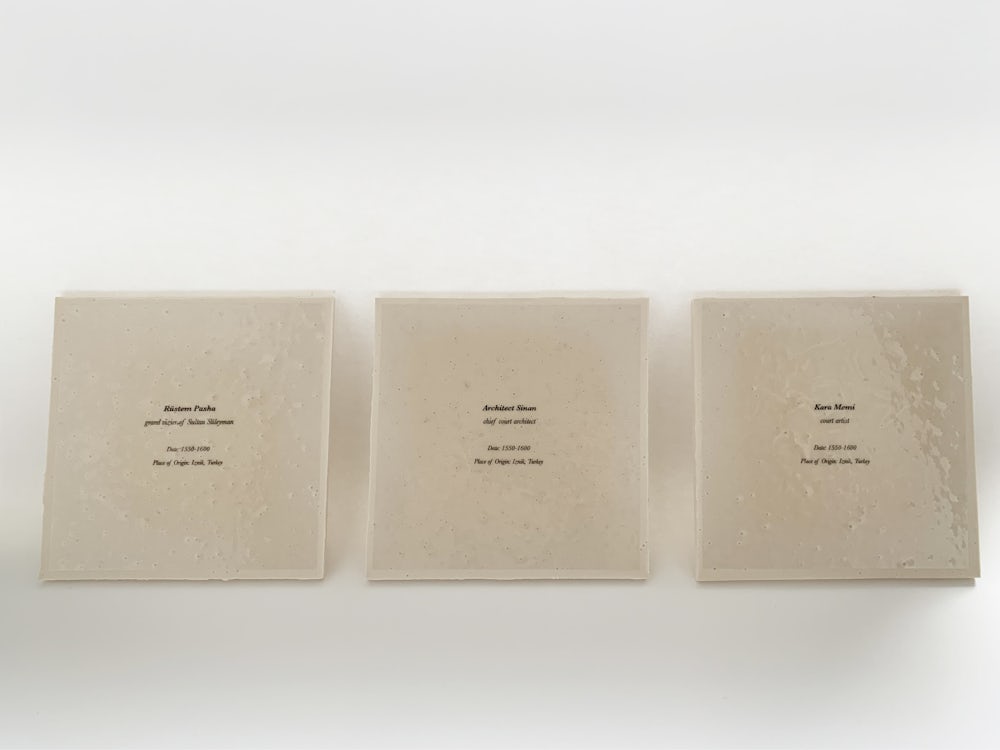

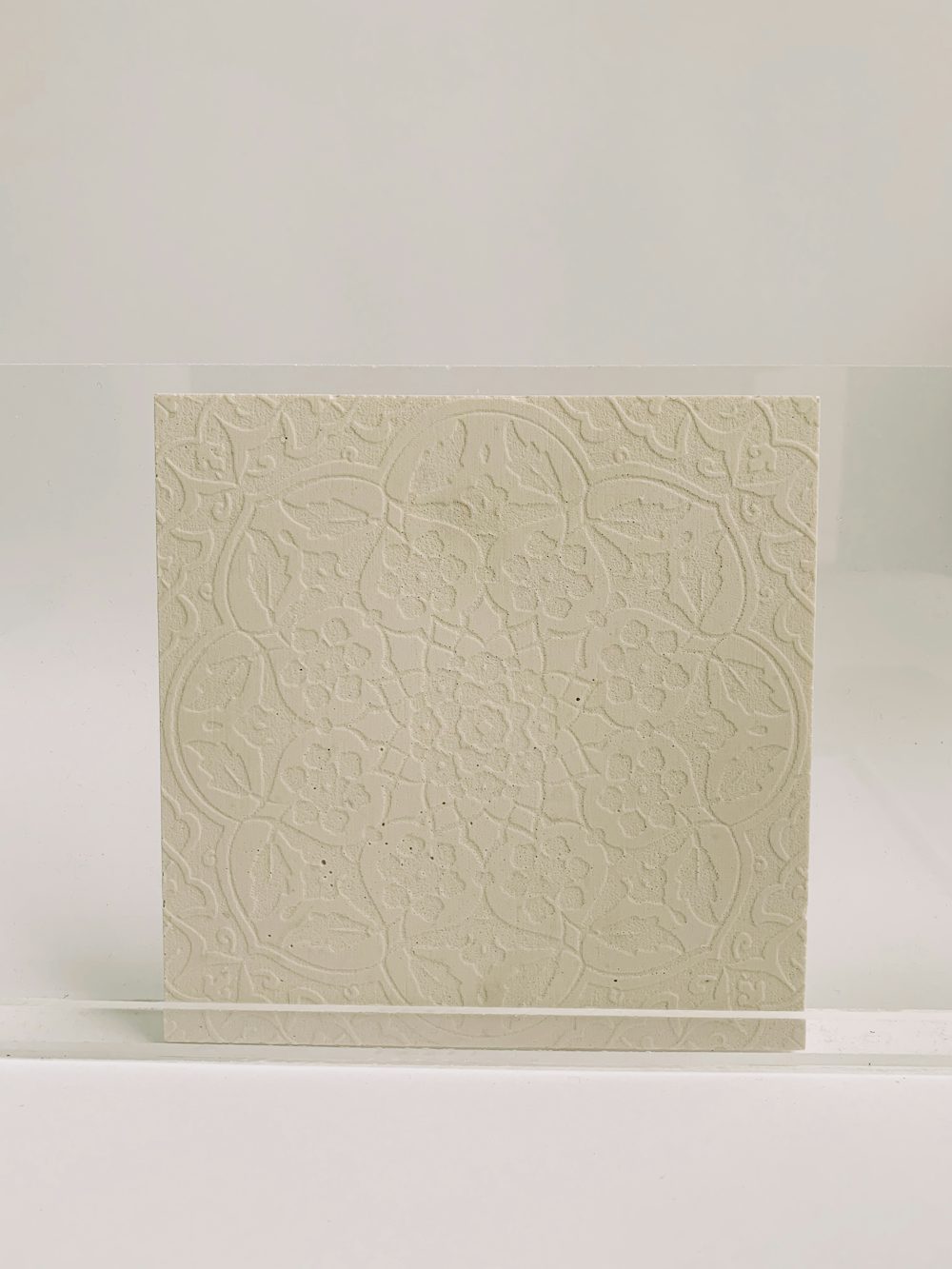

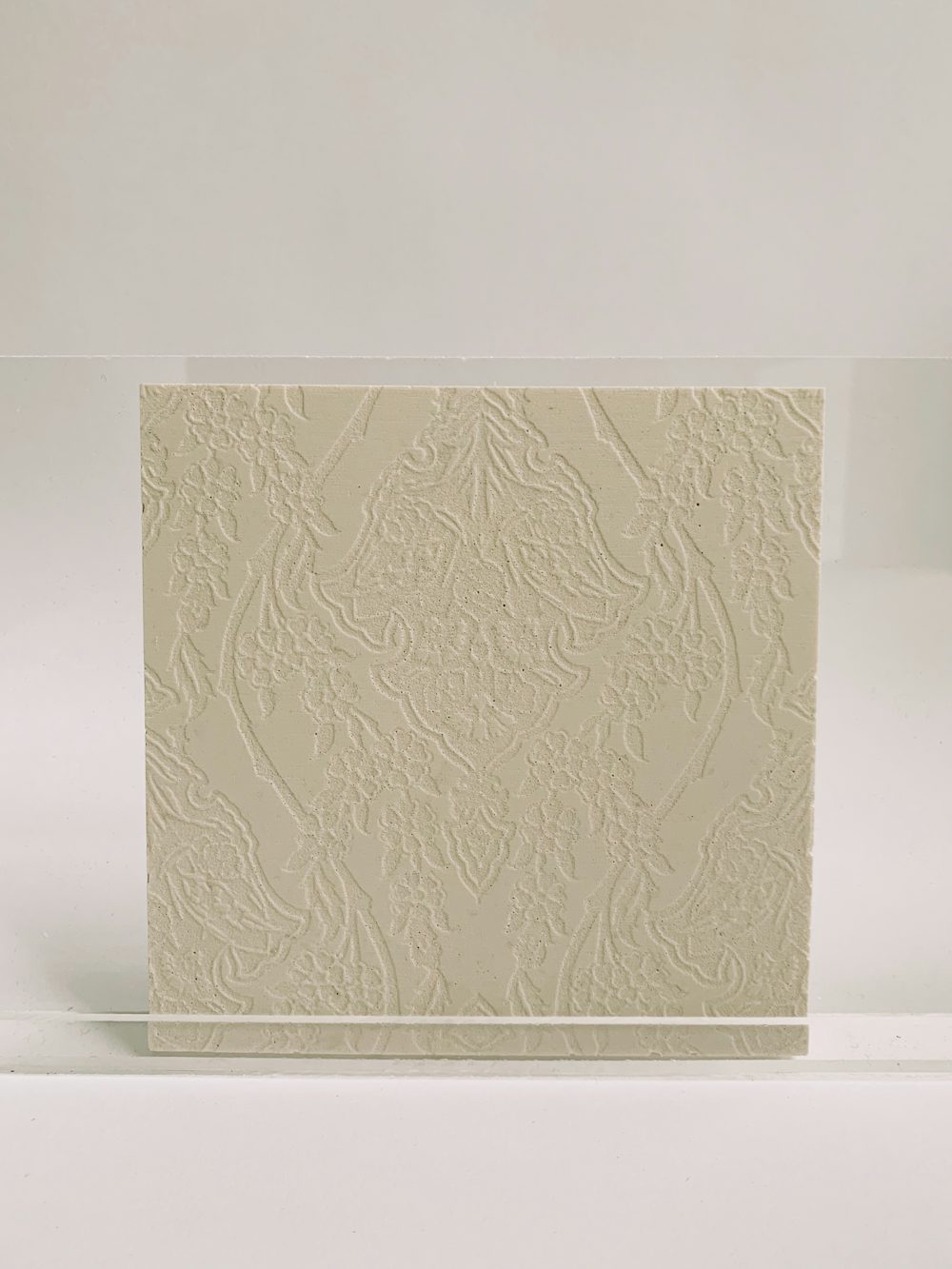

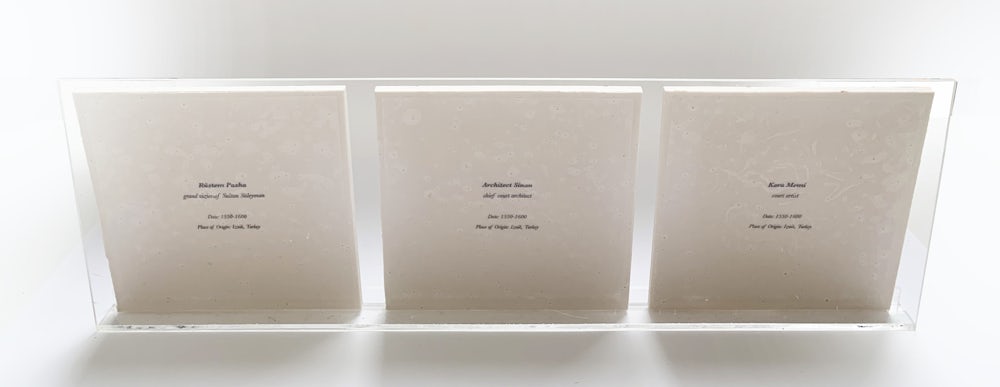

Three Iznik tiles are recreated without colour. By removing the colour -the element that allures the viewer the most- more attention is drawn to the technique, material, surface, form and geometry. The acrylic display, unlike the usual mounting, invites the viewer to see the back of the tile where usually the signature of the artist and origin is recorded but gets lost when mounted on a wall. At the back of the tiles three of the most important individuals are represented; Kara Memi, Architect Sinan and Rüstem Pasha. In doing so, my project criticises how Iznik tiles are normalised in the West because of a fantasy but their meaning and specialty are lost.

British Museum, Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art, London, 2019. ↩

Emmanuelle Gaillard & Marc Walter, A Taste for the Exotic: Orientalist Interiors, New York: Vendome Press, 2011,7. ↩

William Greenwood & Lucien de Guise,Inspired by the East: How the Islamic World Influenced Western Art, London: British Museum Press, 2019 ,14. ↩

Walter B. Denny, Iznik: The Artistry of Ottoman Ceramics London: Thames and Hudson, 2004, 218. Gaillard and Walter, 2011, 202. ↩