Each day 2.5 quintillion bytes of data are created by the internet. Statuses, photos, videos, stories, news, products, porn, memes; and snippets of the most ordinary moments in our lives are written into code, catalogued, archived and consumed. Each one of us has an individual footprint within this landscape of information; a unique set of interactions that describes the things we like, the patterns we adopt and the lives we live. The internet thinks it knows us, it gathers up what it perceives to be our interests and personality traits based upon the the clicks, likes, scrolls and searches we input into our browsers and social medias on a daily basis. The output, I have termed is ‘the digital doppelgänger’, an ever morphing version of ourselves, a digital twin that assists advertisers on their drive to direct brands and products closer to our personal taste. As we are reduced to a set of interests and preferences our behaviour becomes predictable, and with that companies are willing to pay to know what what we will do next and most importantly, what we will consume next. Within this system our digital doppelgänger has become a commodity, something to be bought and sold on the behavioural marketplaces that most of us will never know exist. In the style of surveillance capitalism our raw human inputs to the internet our translated to packages of behavioural data-sets for analysis and sale.

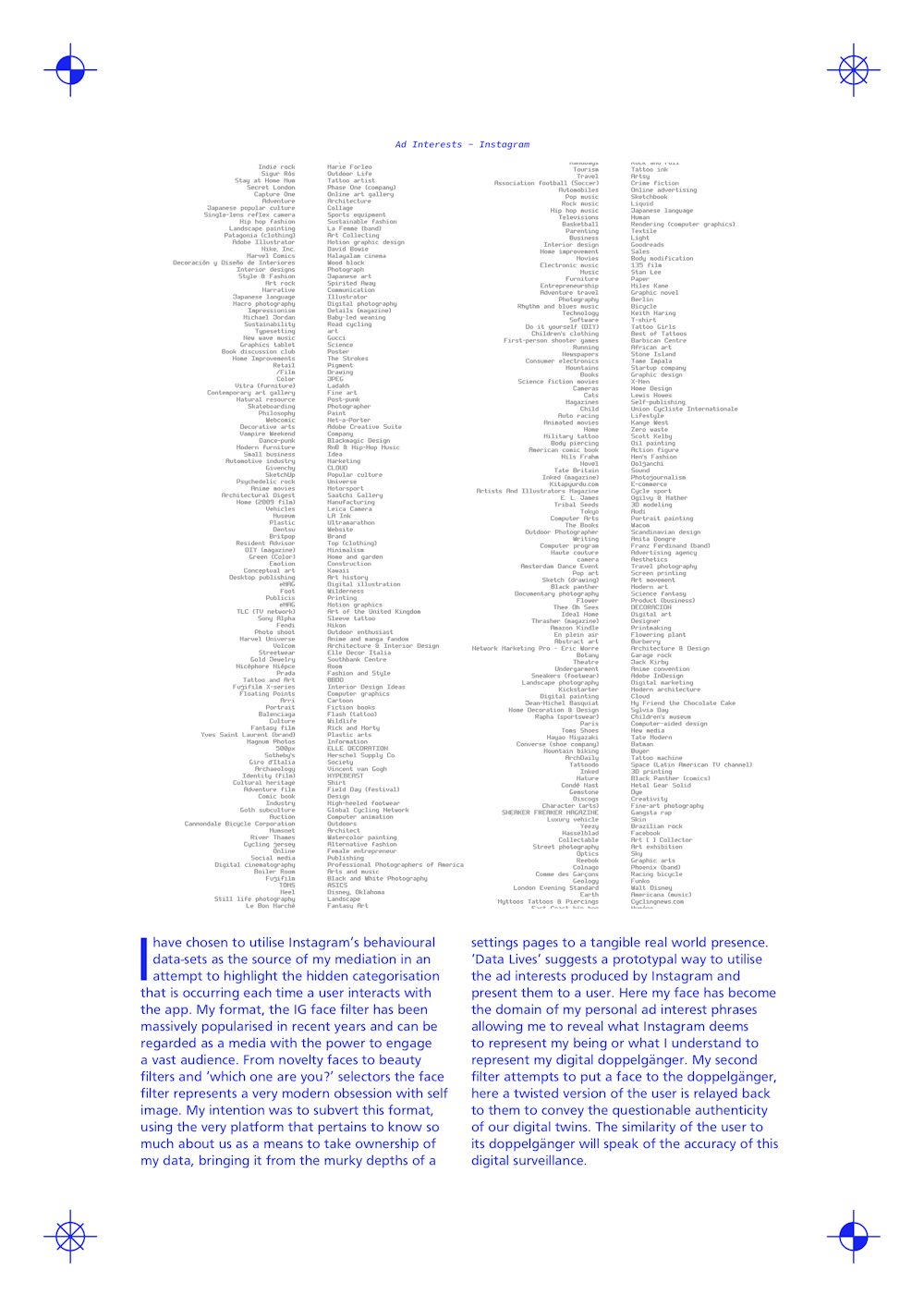

Instagram is the ultimate preferential model; our follows, likes and interactions with the network produce a sophisticated picture of it as a user, which, fed through algorithms, work to present us with more content aligned to what we enjoy. The inadvertent output of this consumption is a wealth of behavioural data that beneath our noses is collated and shared with advertisers. In a little known corner of Instagram’s settings it is possible to pay a visit to your digital doppelgänger. Entering this page reveals the interests this network reduces its user to which for me comprised of a list of 720 words and phrases including reasonably accurate descriptions of my taste such as ‘danish design’ and ‘graphic novels’ to the more absurd guesses including ‘carp fishing’, and ‘stay at home mums’. In truth the vast majority of these categories were things I would happily describe myself as liking. As such, aside from a few randomly misaligned interests my digital doppelgänger would resemble a somewhat authentic version of myself.

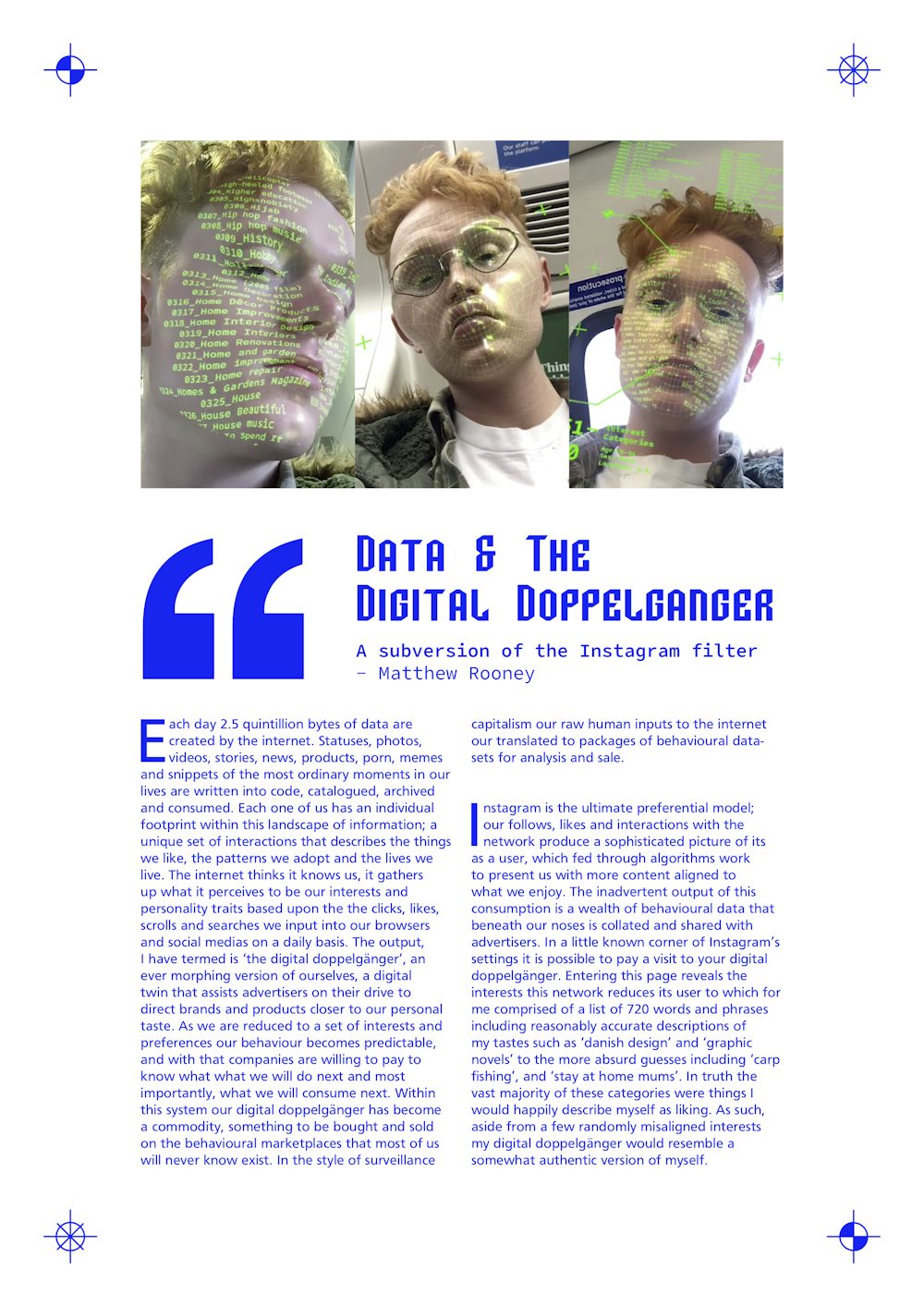

I have chosen to utilise Instagram’s behavioural data-sets as the source of my mediation in an attempt to highlight the hidden categorisation that is occurring each time a user interacts with the app. My format, the Instagram face filter has been massively popularised in recent years and can be regarded as a media with the power to engage a vast audience. From novelty faces to beauty filters and ‘which one are you?’ selectors the face filter represents a very modern obsession with self image. My intention was to subvert this format, using the very platform that pertains to know so much about us as a means to take ownership of my data, bringing it from the murky depths of a settings page to a tangible real world presence. ‘Data Lives’ suggests a prototypal way to utilise the ad interests produced by Instagram and present them to a user. Here my face has become the domain of my personal ad interest phrases allowing me to reveal what Instagram deems to represent my being or what I understand to represent my digital doppelgänger. My second filter attempts to put a face to the doppelgänger, here a twisted version of the user is relayed back to them to convey the questionable authenticity of our digital twins. The similarity of the user to its doppelgänger will speak of the accuracy of this digital surveillance.