Elliot Bourne

"To England, Love from 'Wales' - I Lloegr, Cariad Mawr oddi wrth 'tramorwr'"

Keywords: extraction, colonialism, labour, objects

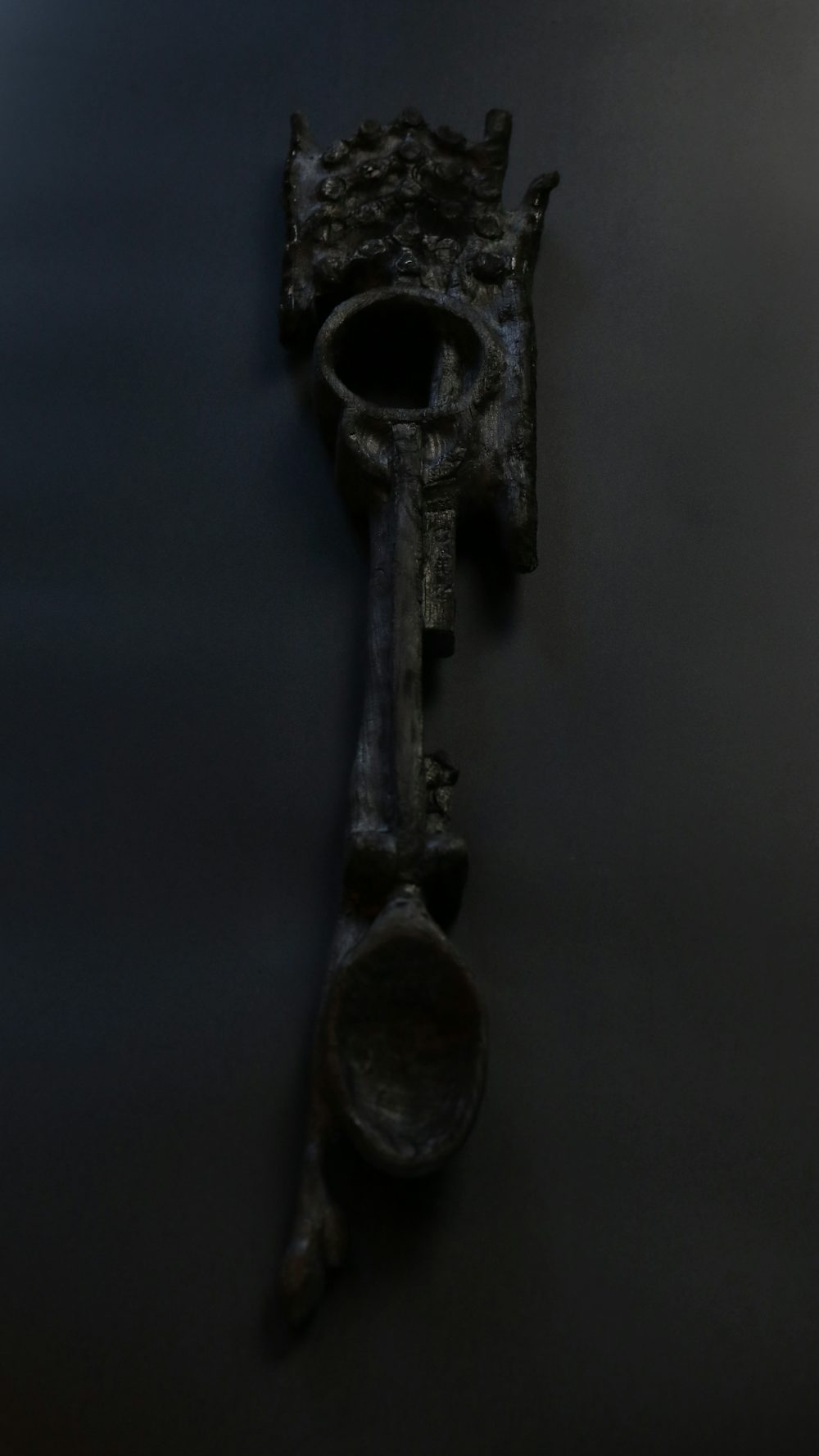

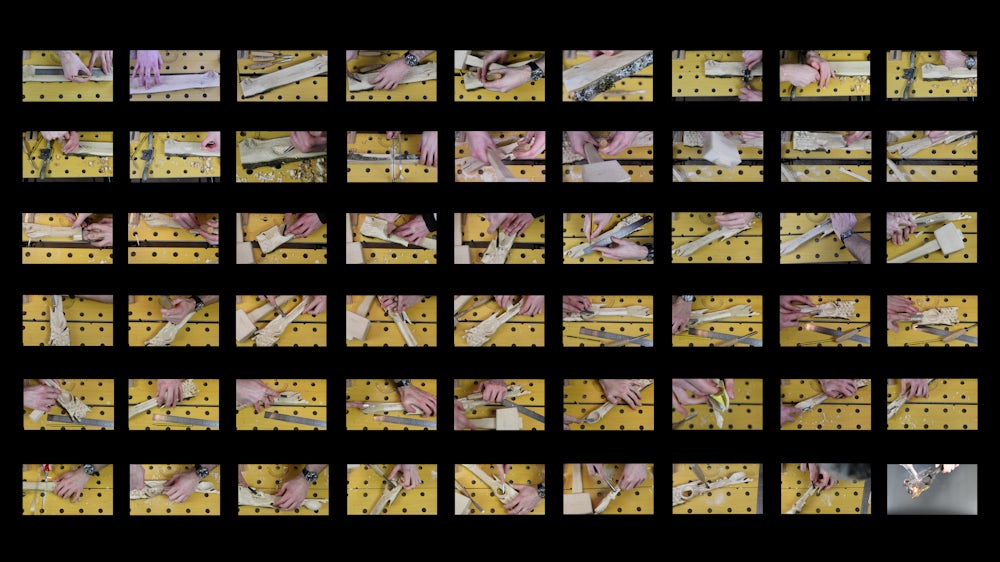

The history of Wales is confused, not often heard and considered uninteresting to most. I however, would refute this. As both a beneficiary of colonisation and a victim, Wales has a productive perspective to add to the conversation on de-colonisation. As Iraqi-born, Cardiff-based artist Rabab Ghazoul, has said, "[...] we in Wales have the capacity for both radical empathy and radical responsibility". In my project, I focus on the Welsh practice of carving and giving wooden spoons as a symbol of love. This practice dates back to at least the 17th Century and forms part of a much wider craft tradition in the country. These spoons are heavily symbolic, historically embodying symbols relating to love and affection; however, contemporary examples include representations of Welsh identity such as dragons and daffodils. It is generally believed that lovespoons were formerly crafted by male suitors and then presented as romantic gifts to the maidens they admired. My lovespoon would be a subversion of this practice, its form and material referencing not a romantic relationship between Wales and England but an exploitative one.

The Welsh 'Valleys', within which is my hometown, has a GDP of 68% the EU average, compared with London's GDP of 614% the same average; this is the greatest inequality in any one country in Europe. There is, of course, a complex assemblage of reasons for this inequality. However, a key aspect is the exploitative mining industry, the extractive economy it created and the void its closure left. Mining practices in Wales date back to the Roman times but burgeoned into a Goliath during the 18th Century Industrial revolution, with the Welsh Ports of Barry and Cardiff becoming the first and second biggest coal exporters in the world by 1913. The mines where this coal came from were predominantly owned by English entrepreneurs creating an extractive economy where the communities stayed poor.

Therefore, I posit the lovespoon as a tool amongst a constellation of other tools or physical artefacts. These include 13th Century oppressive infrastructure, symbolic mock governance, protest instruments, damning government documents, stolen relics, a drowned village and a substitute currency. More importantly, the project highlights how the lovespoon is entangled in a violent practice where wood is extracted from a tree - taken - and its form destroyed through labour. This process in a sense is akin to the violence and extraction of the mining practice. Juxtaposing physical artefacts of extraction and exploitation with a welsh craft tradition, the project seeks to be a culturally specific embodiment of this injustice, referencing the labour exploited and violence performed on the land; a critique of the complicated relationship between the two countries.