Moé Atsumeda

"The Commodification of Religion, Luck and Sacred Rituals"

Keywords: identity, archival practice, consumption, installation, materials, objects, performance

The Commodification of Religion, Luck and Sacred Rituals explores ideas about the commodification of religion, good luck and spirituality. Through the process of modernization, Asian religions have crafted an intimate relationship with the market economy and have undergone a process of commodifying the symbols of religion, which touches upon the notion of luck, protection and spirituality. This process of commodification has transformed as Pattana Kitiarsa states, “key symbols and potent artefacts of Asian religions into economic goods and objects of religious desire in the market of faiths”.1

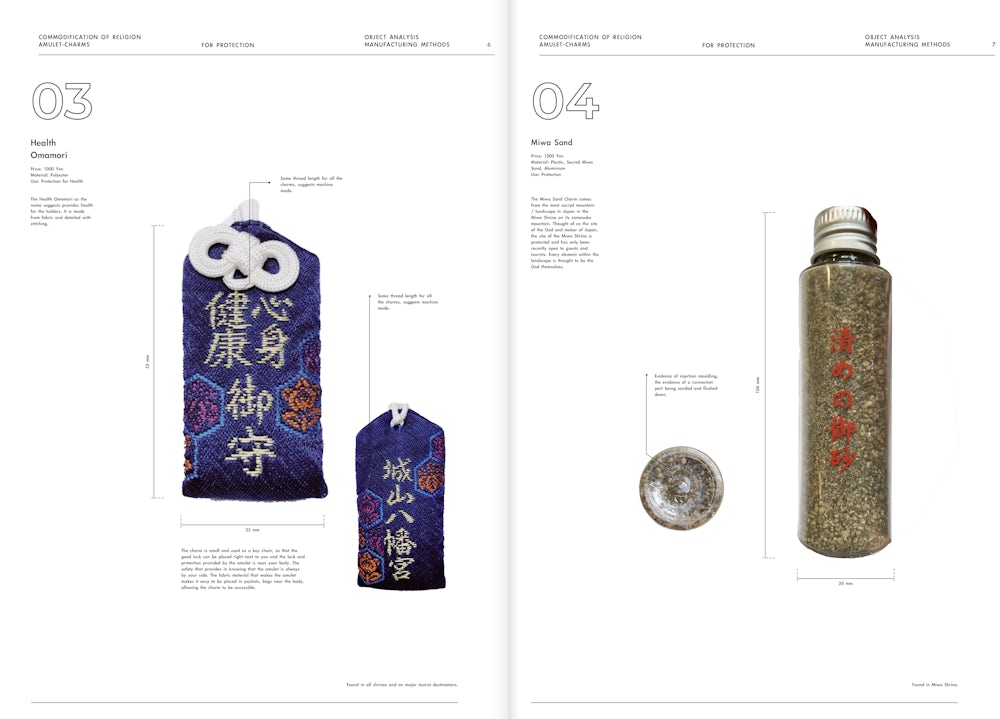

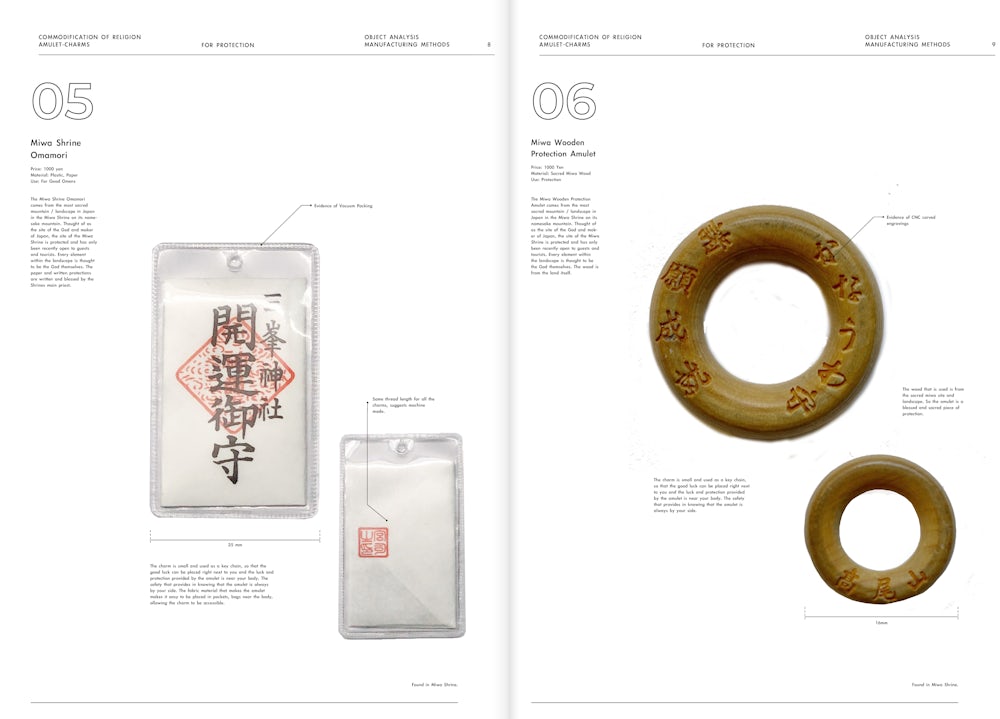

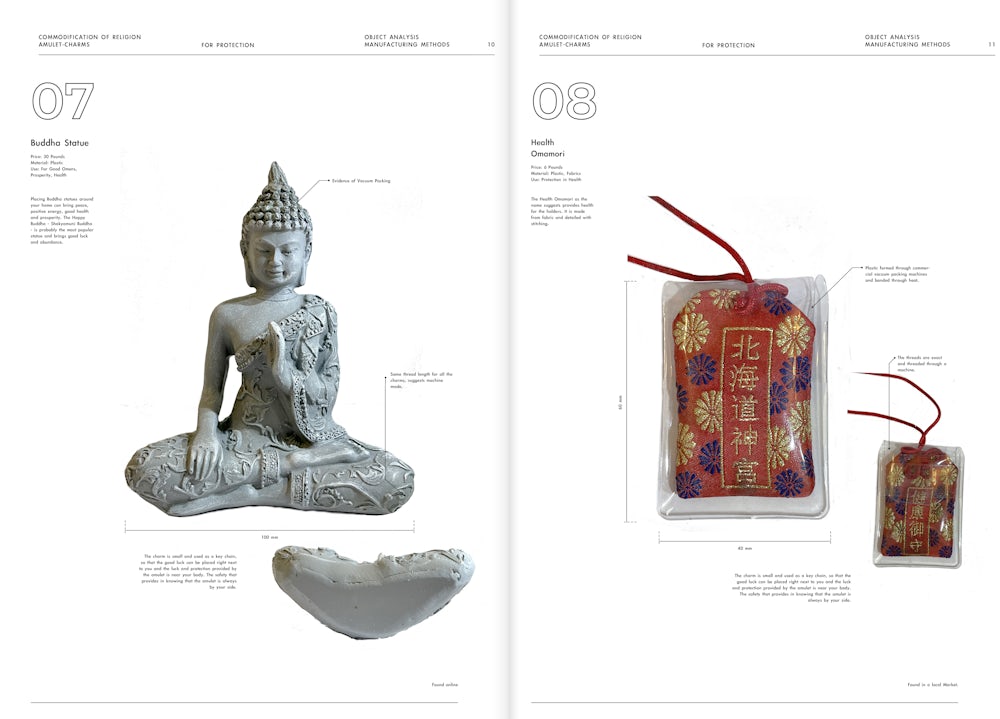

In Thailand, an estimated 1.25 billion dollars’ worth of Buddhist charms are sold every year, with many amulets of faith, produced through the means of mass-production, producing mere imitations of the symbols. The mass-produced, identically made amulets are always bought together with the ritual of closely inspecting and feeling an amulet. In Japan, the sacred object that stemmed this project, a bottle of sand from the most sacred shrine and landscape in Japan, neatly contained in a mass-produced bottle. The process to acquire the amulet shrouded in rules and rituals. Much like in Thailand, the business of selling religion garners an estimated 1.3 billion in many of the larger shrines and for many are their main source of income.

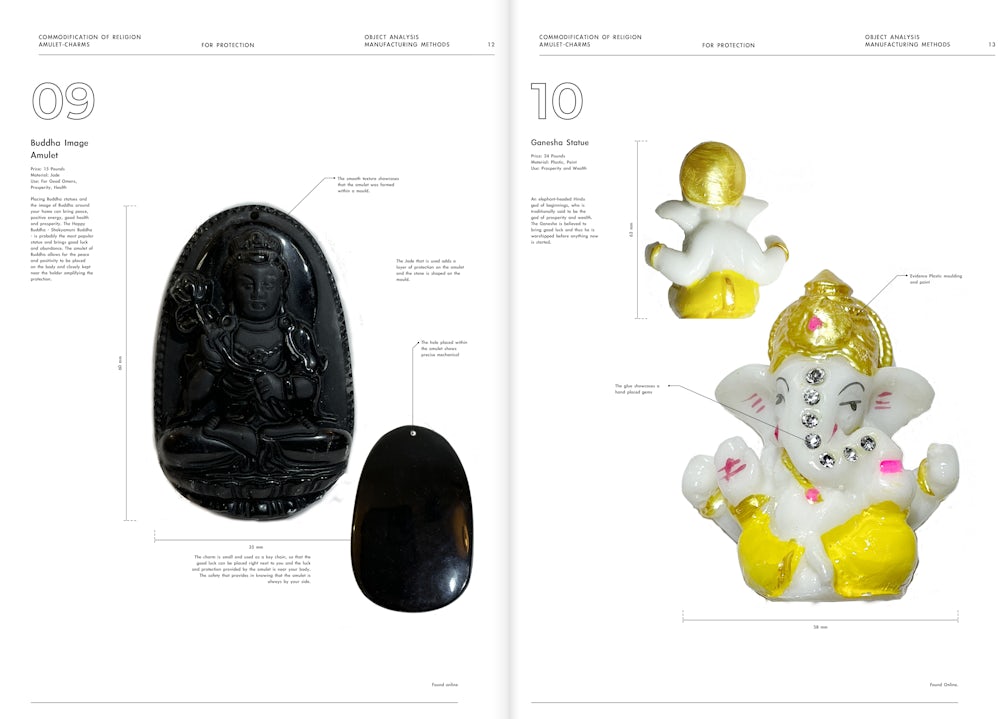

The Commodification of Religion, Luck and Sacred Rituals questions what it means to duplicate and commodify objects of faith, and if the process of mass production and consumerism impacts the embedded story. Does the process of attaching monetary value effect or change the image?

Through the process of duplicating and producing the objects through the method of casting, the project was able to examine acutely the effect of the outcomes. The process of casting allowed a mirroring of the process of the repetitive manufacturing process laboriously, whilst also allowed for an intimate attachment to the production methods which produced the nuanced response showcased within the film. The contrasting notion from the clinical and the personal story of my father’s faith in the rituals scales the grey zones that the commodified objects sits on. The removal of ornamentation and colouring from the religious images through the method of casting, decodes whether even with just the outline and form of the religious symbols such as Buddha and Ganesha, the protection and meaning afforded carry forward.

The project began from the sacred Miwa Sand Amulet, an amulet bought by my father from Miwa Mountain, arguably the most sacred Mountain and site in Japan. His ritual of visiting the mountain every time he visits, and the ritual of passing it on to me when he returns. The act of care when passing and sharing his blessing to his family. His act of care and language of love. The film and the objects tackle the complications of those acts coming from the commodification of religion.

Kitiʻāsā, P. (2012). Religious commodifications in Asia: Marketing gods. London: Routledge. ↩