Ven Paldano

"Our Community Will Not Be Funded"

Keywords: community, moving image, queer methodologies, social media, migration

Brighthelmstone (now Brighton) is a town that boasts a very liberal agenda, despite being developed by wealth from a number of colonial slave masters. Its histories mark a deep avarice of capital expansion, which has led to a strange juxtaposition between bourgeoisie high society, its followers and an assortment of ‘others’ who benefit from the flexed policies of the wealthy. It is a city that now has a penchant for progressive politics, purporting itself to be a safer space for the rainbow population, students and a ‘diverse’ community that delivers only if the individual is of a certain class. Despite being saturated by many nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) and having strong anti-fascist grassroots organising presence, it is a city like many in the UK that struggles to house, offer health support and continues to police its most marginalised community members.

My lived experience is of growing up, working and organising within my QTIBIPoC (Queer Trans Intersex Black Indigenous People of Colour) community in Brighton and being the offspring of migrant parents who settled here once from Windrush and a second time after trying to migrate back to their homeland in the Caribbean, which failed due to work opportunities. This has taught me first-hand how important a small red passport is, additionally how austerity and the hostile environment agenda policy is succeeding in its design brief, at restricting and silencing the most marginalised subaltern into submission.

Many marginalised communities at the mercy of epistemic violence, are backed into a corner where they become dependent on NGOs of the third sector. These organisations sit and mediate between the private and public sector and also spatially within cities. They are the gatekeepers to policy change through their access to a trillion-pound industry of aid, grants, development funds, and self-generating donations. These funds power their predominantly top-down business model, into facilitating community consultations. The information acquired through recording the suffering of precarious members of the community, acts as verification that they are performing a service for the state in acknowledging the marginalised. This proof feeds a chain reaction, in which these organisations, ‘who quench the conscience of the world’, have the evidence that they need to access funding allocated by the state to aid and assist particular groups of the community; knowing that it will likely only ever line the pockets of the NGOs’ employees and not the people who need it.

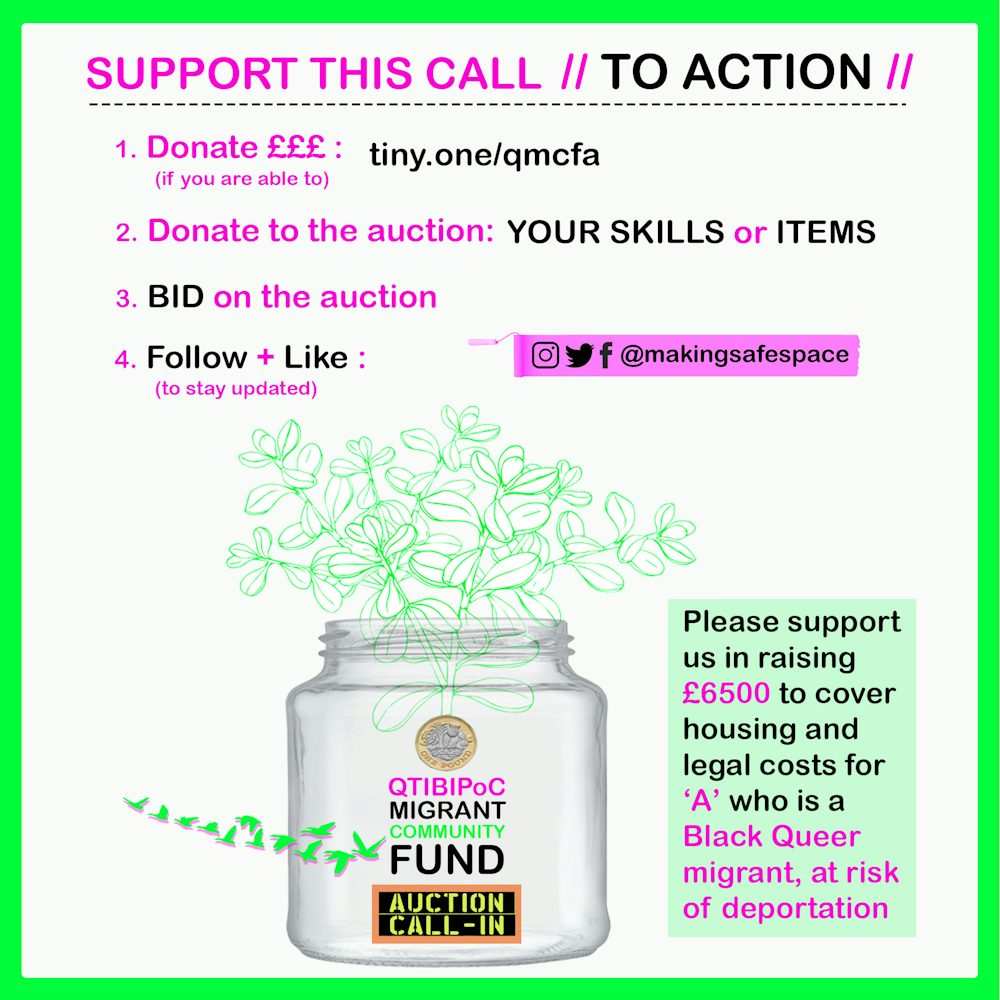

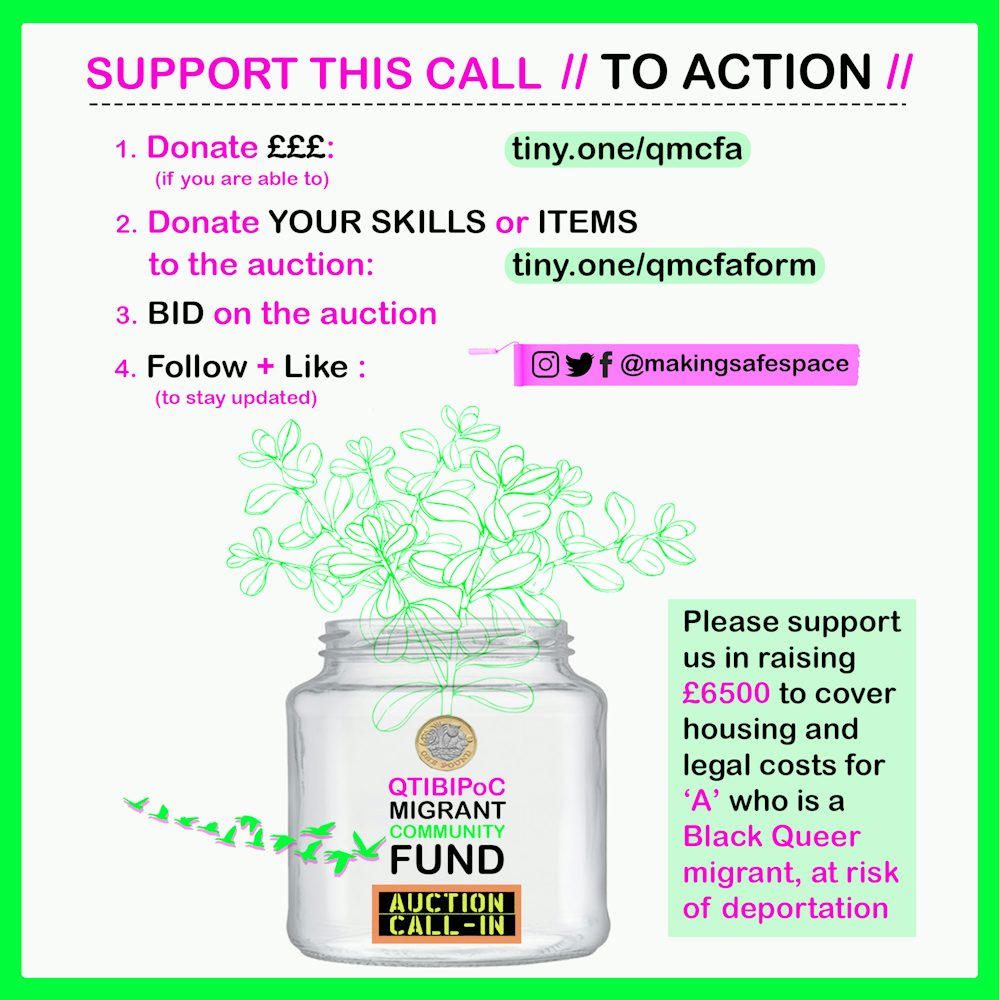

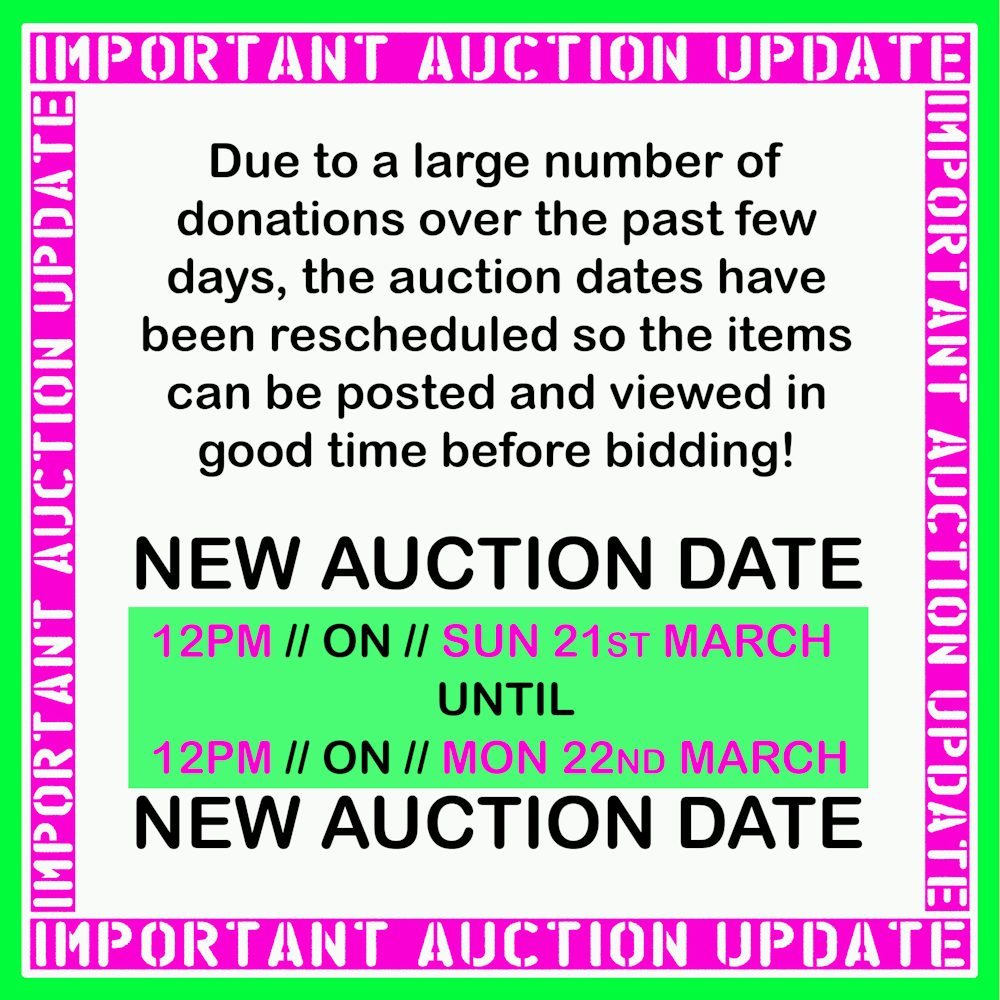

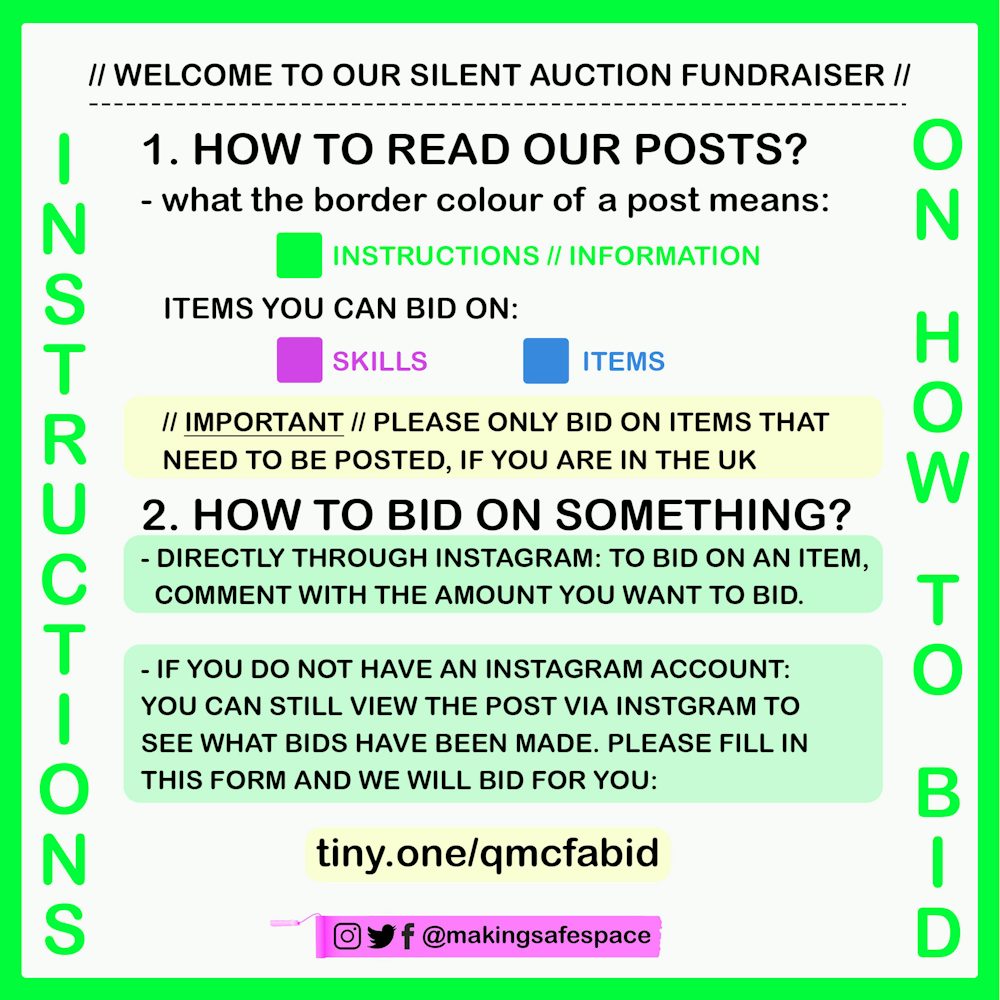

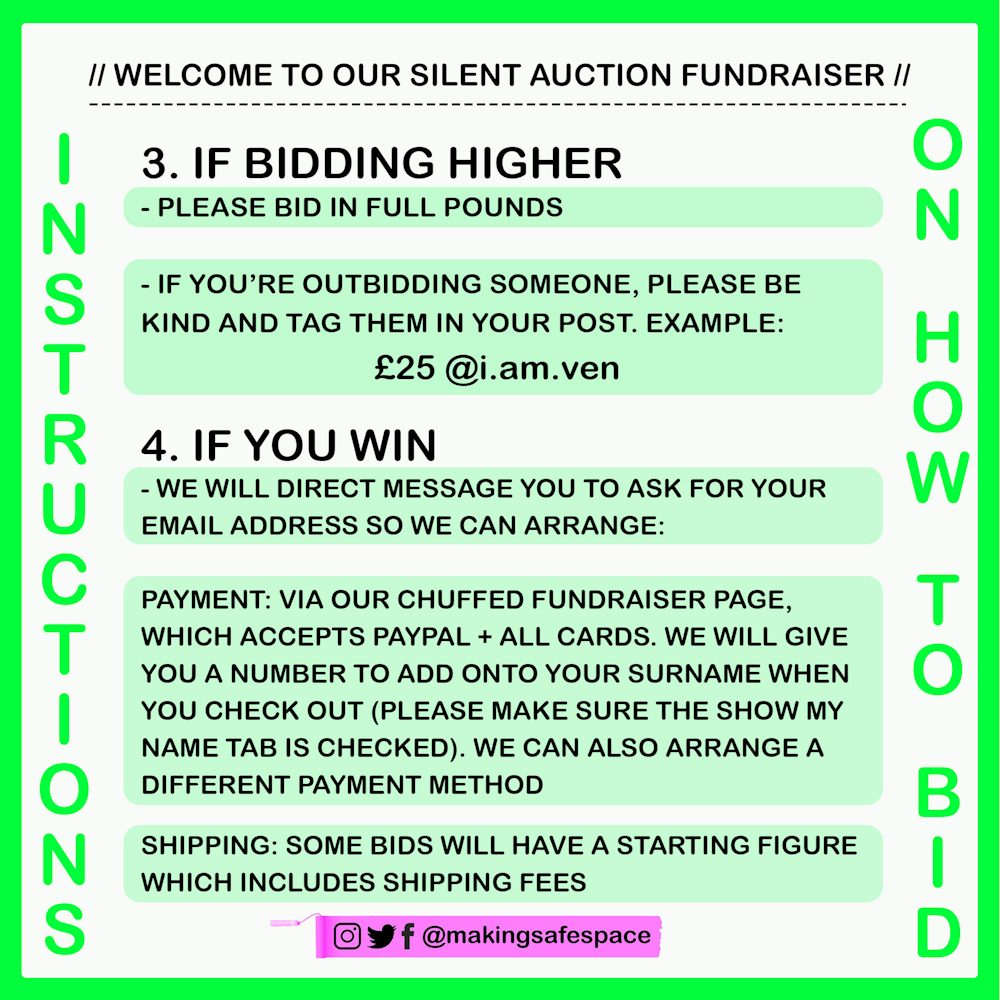

My project documents an alternative to governmental funding bids, inspired by the Susu community saving plans mobilised by the Windrush generation, when banks would not welcome them. I recorded the journey of holding a fundraiser auction with the support of a number of grassroots bottom-up community groups, with the goal of raising funds to support the legal costs of asylum for a black queer migrant. This acts as a community building incubator project, that consciously bypasses the tokenistic idea of charity by utilising interchangeable mutual aid based on a radical queer anarchist structure versus a liberal structure, with the hope of future fundraisers from this video. My strategy for compiling is composed of the recording of the fundraiser auction process as a how-to DIY video, through archiving community engagement to the fundraiser via four online social media platforms (due to COVID-19 – restrictions: Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and email) in response to call-in media posts.