Chandni Patel

"Alternative Archives: In Conversation with the Lansbury Estate"

Keywords: archival practice, textile, materials, identity

‘Moral fabric’, ‘social fabric’, ‘interwoven’ lives, communities ‘bound’, ‘weave’ tales, ‘cloaked in…’ The English language is full of expressions that suggest the importance of textiles in our collective conscious, and the production of textiles has expressed group identities and communities throughout history. The manufacture and use of cultural fabrics continue to generate social bonds around the world and maintain a tradition of knowledge, skills and exchanges in migrant communities. The strengthening of community through endangered cultural practices, namely textile production, is deeply embedded in social structures, materialising intangible concepts such as power, ideology and gender. Historically, textile production has been instrumental in mobilising communities to defy oppressive structures.

The project uses East London housing estates, particularly Aberfeldy Village and the Lansbury Estate as case studies to understand the role and position of an archive. An existing archive of these places features seductive images of a celebrated post war housing estate, and a typically white, working class community. The images posted in the archive depict an artificial lifestyle, ignoring huge swathes of ‘othered’ communities. Staged within a synthetic community, the archive obscures the true idea of place and erases the estates as a real place. Although the image is a fiction, these fictions are made real as they continue to be built into the city.

In the summer I had been involved in collating an archive of textiles, memories and ephemera from the local Bangladeshi community. This archive sat in stark contrast to the existing archive which collected the memories of the traditional, working class, White, east Londoners, and the invocation of the use of this new archive was met with hostility and blatant racism. Celebrating a communities most prized asset only gave way to deep criticism about what the community represented. And by giving a voice to a group that had not spoken before, I, as the archivist, have only deepened the stigma faced when forgotten groups speak out.

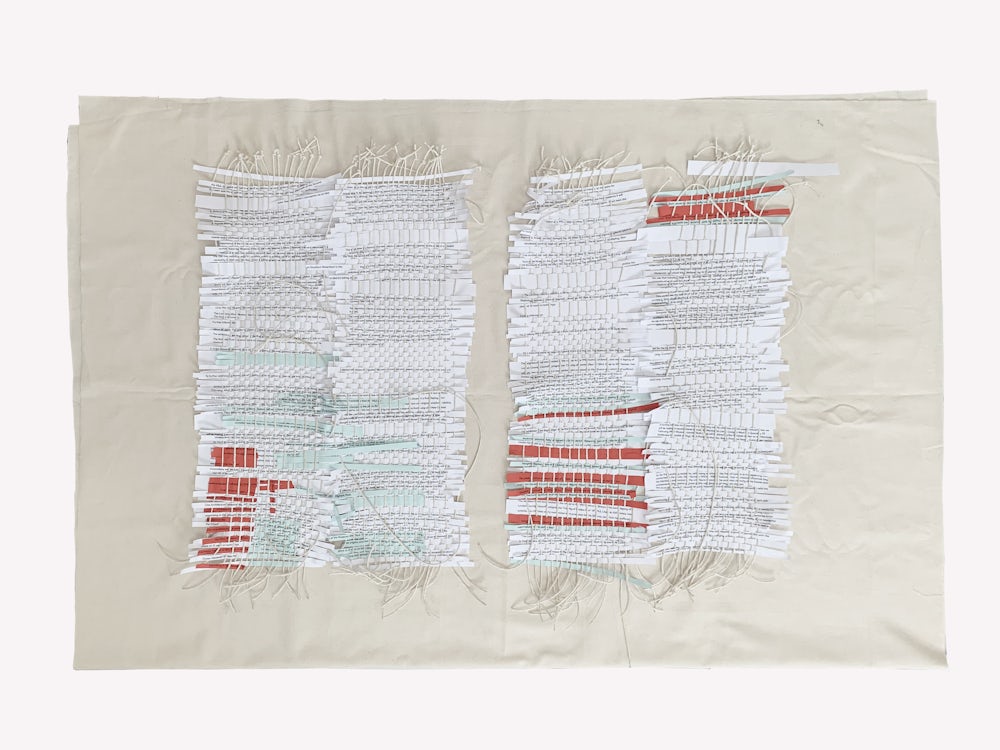

To prevent the inevitability of the cliched image becoming fact, can we compile the histories, stories, cultures and people in the area that an archive ignores. Can we create an object or a method to hijack the archive, can we sneak into the archive, unnoticed or otherwise? Does the archive only host images, photographs and quotes? Can abstract artefacts, newly created methods of weaving narratives also be in an archive? How do we give a voice to those excluded in the archive?

As opposed to creating a new archive, the project seeks to interfere with the existing. If the existing archive employs researchers to define the boundary of what is important, and seeks to collect local histories, can the boundaries be expanded? If the existing archive accepts only certain media typologies, can traditional media forms become reworked through handcraft and the role of physical manipulation?